Discover more from Horace & friends

I’m an absolutist of a sort about poetry and indeed about literature of all kinds. I think that judgements about the quality of writing are not only possible and meaningful, but essential to the cultivation of any real taste or pleasure in literature. I think it’s both patronising and ignorant to maintain otherwise. That means that you can be mistaken about the quality of a work of literature, that you can change your mind, that you can (politely, of course) believe that other people are wrong and try to persuade them in their turn, and — most important and most delightful of all — that reading well is a lifetime’s work, a skill, like any other, which can always be improved.

I taught language and literature (in English, Latin and Greek) for twenty years and I always thought about teaching — whether it was an elementary language class or a doctoral student — as helping both others and myself to read better. There are so many ways to do this, both as a reader and as a teacher, but one thing that comes up quite a lot is the difference between a purely personal response and a critical one. A line of a poem might move me because it reminds me, for example, of a nursery rhyme that my grandmother used to say to me. The particular memory of my grandmother and all that that brings with it is entirely personal to me; but the way that the line echoes a well-known nursery rhyme is not. On the other hand, if I am struck by a piece of writing because it happens to use a word that my grandfather or my first school teacher often used, that might make it very moving for me, but it probably does not have much relevance beyond myself.

As sophisticated readers, we know that coincidences or echoes of this latter kind are not really critically significant in themselves. We teach students, and learn ourselves, to sift them out of formal writing. But all the same, these sorts of associations can be very important to us as readers, and are quite often part of what draws us into a work of literature, even if they are not what keep us there. And perhaps we can talk meaningfully about how literature may provoke such associations — the way that some kinds of poetry, for example, seems designed to elicit them.

These sorts of private associations only multiply, I find, when reading across languages. I’ve mentioned the contemporary French poet Gérard Bocholier before (most recently in this post), as I’ve been reading him slowly but steadily for a few months now. Today I thought I’d offer you one of his poems which I found particularly powerful in the way that it prompted, for me, both the sort of associations which I think we’d all be happy to acknowledge as allusions or part of the poem’s frame of reference, but also a series of other, increasingly personal or specific ones — the part that, perhaps, we don’t usually “say out loud” when we are talking formally about poetry. I can’t speak for M. Bocholier, but it seems to me that the strength of his poetry lies partly in the way that it creates space for these reactions as well.

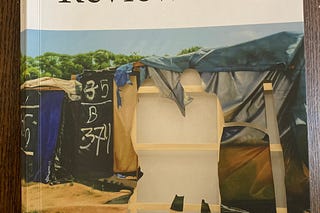

Here is the poem, which is from p. 65 of his collection Nuits. This collection is divided into two parts, the ‘Nuit d’Emmaüs’ (‘Night of Emmaus’) and the ‘Nuit de Saul’ (‘Night of Saul’, referring to the story of Saul who became Paul).

Une paume odorante sur ma nuque

C’est l’heure où le jour verse

Sa coupe d’or

Sur les terrasses

Quand brillent aux grillages

Les prunelles des volubilisLes ouvriers sont déjà loin

Derrière les tertres

Patience bientôt je vais rejoindre

Les vendangeures de la lumière

For those with no or little French, let’s start with a completely literal translation:

A scented palm on the nape of my neck

It's the hour when the day pours out

Its cup of gold

On the terraces

When shine from the fences

The eyes [or berries] of the volubilis.The workers are already far away

Behind the mounds

Patience soon I will join

The harvesters of the light

I think the most obvious thing to say about this lovely poem is the way in which it combines a very distinctively French context — of the grape harvest in a vineyard — with scripture. Several elements of the agricultural context aren’t translatable, because England doesn’t really grow wine, and winegrowing has certainly never had the same cultural role as it has in France. A vendangeur, for instance, is specifically someone picking grapes: there’s no single word for that in English. Terrasses are the terraces of a vineyard, designed to make sure each row of vines gets enough sun. Terrace exists in English, but I don’t think the native English reader encountering the word thinks immediately of a vineyard upon a slope, but rather of something like a colonnade or portico (or perhaps the terraces of a football stadium).

The sense of a scriptural context is conveyed partly by the collection as a whole. This second part of the second section of the book is headed by a scriptural epigraph, from the Acts of the Apostles 9.8, describing how Saul, up to that point an enthusiastic persecutor of Christians, is dazzled by a blazing light on the road to Damascus, and realises he has lost his sight: ‘Saul got up from the ground; but even though he opened his eyes, he saw nothing.’ This whole sequence of 22 poems, of which this is the nineteenth, are told, as it were, in the darkness.

Setting the poem in a vineyard when the light is low, at the end of the afternoon — if that’s what it is implied by the moment when the day pours out its cup of gold — also immediately recalls the parable of the workers in the vineyard in Matthew 20, which you can read here. The speaker of the poem, who will go and join the ‘grape-pickers of the light’ only, apparently, late in the day, further recalls the parable, in which the workers hired at the end of the day, who have laboured only for an hour, receive the same payment as those hired at the start. Several individual elements of poem’s vocabulary also have scriptural echoes. The day’s coupe d’or (‘cup of gold’) describes the sunlight, but also suggests the Eucharist, especially when combined with the verb verser, to spill or pour out, which is the verb used in the contemporary French version of the Catholic Mass at the consecration to describe the blood of Christ, versé pour vous (‘spilt for you’).

The lovely Latin word volubilis (we’ll come back to that) is the French term for a convolvulus, flowering plants like bindweed. Prunelles can be the fruit of the prunellier, the blackthorn or sloe, with its dark berries. Perhaps we are meant to remember that, because sloe-berries look a bit like grapes. But prunelle can also mean the pupil of the eye, and I think it is the shining ‘eyes’ of the convolvulus flowers that are probably meant here — eyes are relevant, of course, because at this point in the sequence Saul cannot see. And prunelle is also the standard French translation for the beautiful phrase from Psalm 17 traditionally translated in English as ‘the apple of the eye’: ‘Keep me as the apple of the eye, hide me under the shadow of thy wings’.1 So in that sense prunelles are something uniquely precious and to be protected. This links back to the intimate tenderness of the first line — the scented palm on the nape of the neck.

Nuque is the ordinary word in French for the nape, but as so often its English cognate is used only in a technical sense. Most pregnant mothers are now offered a scan to measure the nuchal fold of their unborn baby about three months into pregnancy, because a thicker than usual fold at the back of the neck at this stage is associated with various congenital problems. So for me, as a woman who had babies in the UK fairly recently (Happy Birthday by the way to my eldest son, who is 12 today), this ordinary French word activates a whole set of memories about the very particular anxieties and mysteries of pregnancy. This is the sort of association which is surely, critically speaking, invalid: nuque is an ordinary word in French. But at the same time it seems oddly appropriate — to the intimacy of the poem, to the way the sequence explores different kinds of “seeing” and knowledge, to the darkness of the womb and Saul’s period of blindness heralding rebirth, and to the implied themes of life and death.

Volubilis (like convolvulus) literally means ‘turning’ or ‘twisting’ — the way a vine twists its way up a tree or a fence: it’s a Latin word that has been adopted directly into French. When I first read this poem, I realised that volubilis must be the French for some kind of climbing or twisting plant, but I didn’t know which. I did though have a strong association with the word as a Latin adjective — and, much more specifically than that, as the final word in one of my favourite of all Horace’s odes, in fact the very first piece of Horace I ever attempted to translate myself, as a teenager, Odes 4.1. In this poem, the speaker attempts to refuse Venus, saying he is too old for love affairs (and, by implication, erotic poetry), and suggesting that she approach a promising younger man, Paulus Maximus, instead. He tries to claim that he is no longer moved by either boys or women, nor by wine or flower garlands (traditional further elements of erotic and sympostiastic verse). But immediately after making this declaration he is forced to admit the truth:

me nec femina nec puer

iam nec spes animi credula mutui

nec certare iuvat mero

nec vincire novis tempora floribus.sed cur heu, Ligurine, cur

manat rara meas lacrima per genas?

cur facunda parum decoro

inter verba cadit lingua silentio?nocturnis ego somniis

iam captum teneo, iam volucrem sequor

te per gramina Martii

campi, te per aquas, dure, volubilis.

One of my favourite translations of this poem is by Ben Jonson. Here is his version of these final three stanzas:

Me now, nor wench, nor wanton boy,

Delights, nor credulous hope of mutual joy,

Nor care I now healths to propound;

Or with fresh flowers to girt my temple round.

But, why, oh why, my Ligurine,

Flow my thin tears, down these pale cheeks of mine?

Or why, my well-graced words among,

With an uncomely silence fails my tongue?

Hard-hearted, I dream every night

I hold thee fast! But fled hence, with the light,

Whether in Mars his field thou be,

Or Tiber's winding streams, I follow thee.2

Jonson’s version is excellent, but it does not attempt to reproduce the extraordinary effect of the word-order in the final lines of the poem that puts the vocative of the word for ‘hard’ (or ‘hard-hearted’), dure, in the middle of a closing phrase describing the water: te per aquas, dure, volubilis. It is very typical of Horace’s style to end a poem with a single, ordinary adjective which is mysteriously transfigured by its position. (I have written a bit more about Horace’s lyric style in a few places, but especially here.) We end the poem caught apparently permanently in the contrast between the hardness of the boy Ligurinus, who will not be wooed, and the twisting flow of the waters.

Odes 4.1 was once quite a famous poem, but it’s not in the top three or four best-known Horatian odes today, and not that many people now, even among poets, have even a few lines of Horace in their head in Latin. In the end, I don’t think it’s likely that the word volubilis in Bocholier’s poem is alluding to the yearning of Odes 4.1. I wouldn’t make such a claim in any formal analysis and I wouldn’t mention it if I were teaching any more than I would share my experiences of the nuchal translucency test.

But then just two pages on in Bocholier, we find this little poem, printed in italics:

Le faon qui s’est perdu

Rôde sur la lisière

Joie et peur se répondent

Aux veines de son couLes grands pins l’épouvantent

Les vents à la voix rauque

On entend qui grelotte

Enfoncée sous les mousses

La cloche d’une source

Here’s a literal translation:

The fawn that is lost

Strays on the edge

Joy and fear answer each other

In the veins of his neckThe tall firs make him tremble

The winds with their hoarse voice

We can hear it shivering

Sheltered beneath the moss

The bell of a spring

This poem deserves a discussion of its own, but in this case the link to Horace Odes 1.23, another poem about the courtship of a reluctant beloved who does not wish to be caught, is I think pretty undeniable. (You can read Horace’s ode in both English and Latin on this page.) It’s not a translation, exactly, but it’s not very far removed from one either. And there’s the neck again! There does seem to be a connection between Bocholier’s description of the relationship to the divine and the erotics of courtship and predation in Horace. So perhaps it is fair to say that the most personal and apparently random of the associations we make when reading very carefully can sometimes have the quality of an intuition, the scent of a palm for an instant on my neck.

I’m afraid I don’t know very much about the history or connotations of the various French translations of the Bible, but here are the four I checked: ‘Garde-moi comme la prunelle de tes yeux ! / Cache-moi bien à l’abri sous tes ailes’ (BDS); ‘Garde-moi comme la prunelle de l'oeil; Protège-moi, à l'ombre de tes ailes’ (LSG; NEG 1979; SG21).

Subscribe to Horace & friends

Thoughts on poetry, translation and related matters.

Here’s Basil Bunting’s version - an ‘overdraft’, not a strict translation - unpublished in his lifetime:

Like a fawn you dodge me, Molly,

a lost fawn.

A breath of wind scares her.

Leaves rustle, or a rabbit

stirs, and her heart flutters,

her knees quiver.

But it’s me chasing you, Molly,

not a tiger, not to tear you.

Let mother go,

you’re old enough for a man.

I’m reading in between many tasks during Thanksgiving prep, but I wanted to let you know how much I appreciate your scholarship!