How come, Maecenas?

Today’s post is mostly about Horace — with some Wyatt and Jonson at the end. As any keen Horatians among my readers will know, the dictum that poetry should be both beautiful and useful comes from Horace too, so it is appropriate that I heard just this morning that a little collection I’ve edited, Poems Beautiful & Useful, is now available for order from the very exciting new Headless Poet press run by Jem. This is a selection of the kind of poems that were most popular in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, drawn from both manuscript and the obscurer reaches of print. Several have not been published before, and most of them are not well-known. I am proud and delighted to be the editor of Headless Poet’s very first publication. Jem has a whole series of publications planned for this year, all ‘introductions’ of one kind or another — definitely worth keeping an eye on.

The start of Horace’s first satire is one of the great openings in literature:

Qui fit, Maecenas, ut nemo, quam sibi sortem

seu ratio dederit seu fors obiecerit, illa

contentus vivat, laudet diversa sequentis?How come, Maecenas, that no-one can just

Live content with his lot, whether it comes

His way from choice or chance, but rather must

Admire all those who follow other paths?

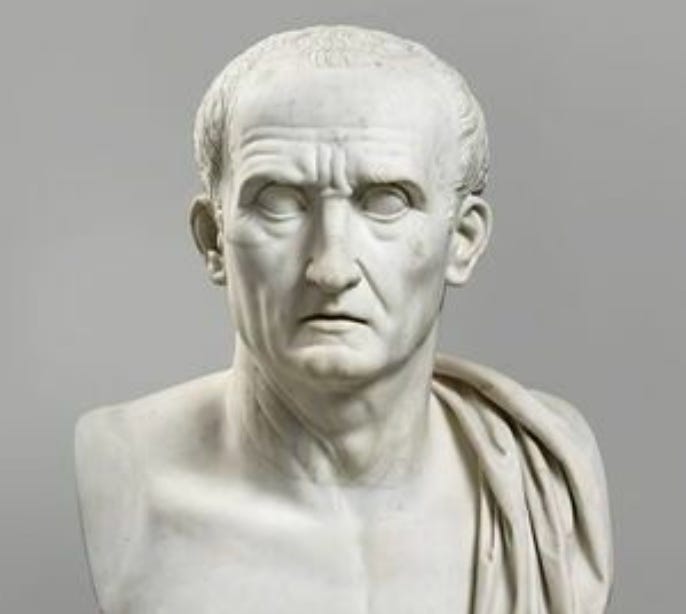

Horace is writing in hexameter, the epic metre, but he writes here, quite naturally, as if he is speaking, or writing a letter to a friend. This is the idiomatic Latin of conversation: in the first line alone the words qui fit (‘how come?’) and nemo (‘nobody’) are, as the commentaries put it, ‘unpoetic’. That ‘Maecenas’ is a dedication, of course — and a massive name-drop — but it’s also remarkably blunt: so much so that many translations fudge it, putting in a ‘dear Maecenas’ or something like that. As Kirk Freudenburg puts it, it’s ‘the least elaborate dedication in all Latin literature’. Horace puts Maecenas in his very first line — as he does in most of his published collections — as a mark of respect. But at the same time he shows that he can address him informally, and even, perhaps, risk offence: most of the poem is about the pointlessness and moral danger of hoarding great wealth, and Maecenas was notoriously wealthy.

As well as his wealth, Maecenas was already famous both for his proximity to political power and for his cultural patronage. As patron of Virgil, Varius and (slightly later) Propertius as well as Horace, his name very quickly became synonymous with poetic patronage and poets have been lamenting the lack of such a figure ever since his death. As Spenser puts it in his Shepheardes Calender:

But ah, Maecenas is yclad in clay,

And great Augustus long ago is dead:

And all the Worthies liggen [lie] wrapp’d in lead,

That matter made for Poets on to play:

In French, Maecenas’s name has passed into the language: un mécène is the ordinary word for a wealthy patron of the arts. There are related words in many European languages.

Published in around 35 BC, the first book of Satires was Horace’s first published work. The date makes it firmly pre-Augustan: the decisive battle of Actium, at which Octavian (who became Augustus) defeated Antony and Cleopatra was still four years away. Horace was writing in the uncertain times of the second triumvirate, between the Battle of Philippi in 42 (at which Horace himself had fought on the losing side) and Actium a decade later. Most of the Latin works we think of as the classics of Rome were yet to appear, although Horace is audibly building upon the achievements in hexameter of Catullus, Lucretius and — especially — the early Virgil of the Eclogues. Virgil’s collection of pastoral poems, with its dense array of allusions to the fashionable Hellenistic Greek poets Theocritus and Callimachus in particular, had only recently come out. (The collection was probably completed around 37 BC.) Virgil himself puts in an appearance in Horace’s fifth satire, and the ten poems of the first book of Satires are in various ways a kind of uneasy response to the ten poems of the Eclogues.

All the same, it’s hard to imagine two contemporary ten-poem collections more different than the Eclogues and Satires 1. The Eclogues are dizzyingly beautiful, but they also often sound like calques or translations of Greek and they contain many recognisable and extensive imitations of specific Greek poems. (The same is true of a lot of Catullus’ hexameters.) Nothing in Horace’s first satire sounds like a translation of Greek; on the contrary, these are some of the very first hexameters — a metre native to Greek — to sound completely Latin.

Indeed, the very first words, qui fit — how come? — introduce a peculiarly Latin idiom. I mean that this phrase is everyday speech — not at all the higher register of poetry — but also that both these words have a distinctive linguistic history. As anyone who’s taught a language knows, the most ordinary idioms are often the hardest to explain, grammatically and syntactically. Here the opening quī is not, as you might assume if you have a bit of Latin, quī as in ‘who’, the nominative masculine singular or plural of the relative pronoun. This is an older form, preserving an ancient ablative or probably rather instrumental formation, and here used adverbially to mean ‘how’ (i.e., ‘by what’).1 Anyone who has paid attention even to their own native language will have spotted this kind of ‘fossilized’ element: forms that have fallen out of everyday speech are commonly preserved in the set phrases of standard idioms. Examples in English include phrases like to and fro, and fob off: any native speaker knows that fro there means ‘from’ and that fob means something like ‘trick’ or ‘deceive’, but neither of these words are in active use in Standard English. I wouldn’t say ‘I’m just on my way fro the shops’ or ‘I think you fobbed in that game of cards!’

What about the second element of qui fit? Fit is the third person singular of the verb fio, which is the verb used in the present and imperfect tenses for the passive equivalent of facio. Facio means ‘do’ or ‘make’, and fio means ‘happen’, ‘be done’ or ‘becomes’. But there are several oddities about fio. To start with, fio is obviously an active form — the -o ending in the first person singular is the active ending in Latin (as in Greek); the passive equivalent would be -or — although it functions as the ‘passive’ of facio, and it does indeed have an infinitive (fieri) that looks passive. So in most of its forms it’s a bit like the opposite of a deponent verb (those Latin verbs like sequor, follow, which, as generations of students have memorised, ‘look passive but are active’). As one reference work puts it, ‘the usual explanation is that the active inflection points away from an underlying passive’, which, as explanations go, could perhaps be clearer. If you go right back to the Rigveda — containing the earliest extant form of Sanskrit — you can find some possible linguistic parallels.2

Horace is asking ‘how come’ people find it so difficult to be satisfied with things as they are; or, as Sanadon puts it in his seventeenth-century commentary, ‘La conduite des homes est une énigme’ (‘The conduct of men is an enigma’). In this first poem he goes on to apply this observation mainly to the acquisition of wealth and power; the second poem mainly to sexual behaviour; the third poem to the necessity for mutual toleration in matters of friendship.

Emily Gowers, in her excellent commentary on the first book of Satires, cleverly points out that Horace’s question “how come?” applies not only to his general query about the mysterious contradictions of human nature, but also to himself: how did he, Horace, get here — to the point of addressing Maecenas so informally? The first book of Satires is full of anecdotal and (apparently) autobiographical detail and has long been one of the richest sources for any “life of Horace”. As a book it surely is in part about how he “got here”.

But for me qui fit is a question about Latinity as well: how come, Maecenas, that Latin poetry has reached this point — suddenly able to do this in hexameter, and poised upon the brink of all the extraordinary subsequent literary achievements of the following 25 years. By the time of Horace’s death in 8BC, we would have the Georgics, the Aeneid, the Odes, Epistles and Ars Poetica, the elegies of Propertius and Tibullus, plus Ovid’s Amores and Heroides. Qui fit? indeed.

And Horace keeps coming back to that qui fit. It recurs as eo fit at line 56, almost exactly half way through the poem:

eo fit,

plenior ut si quos delectet copia iusto,

cum ripa simul avolsos ferat Aufidus acer.so it goes —

whenever you take pleasure in excess,

Aufidus, that narrow stream, will swell

and sweep you and the bank away together

and then again at line 117, the final sentence of the poem proper (lines 120-1 are a kind of coda):

inde fit ut raro, qui se vixisse beatum

dicat et exacto contentus tempore vita

cedat uti conviva satur, reperire queamus.So it happens that a man who says he’s had

a happy life and, now his time is up,

leaves like a well-fed guest, content — well that

man’s, if we’re honest, awfully hard to find.

Horace’s achievement in the Satires is the kind of literary step forward that seems natural — even obvious — once someone has done it. These sort of formal innovations can become so foundational to a literary language that it’s hard to see back behind them: trying to imagine Latin poetry without the mastery of the hexameter that was achieved by Horace and Virgil is a bit like imagining English verse without the sonnet or the iambic pentameter. You have to think yourself back behind that moment to see what a step forward it was: in this case, the marriage of the epic line and conversational Latin; the well-educated parvenu, not long since on the losing side, chatting directly to the aristocratic Maecenas, one of Octavian’s most effective allies. The formal and the social achievements are linked. As Emily Gowers puts it, ‘Although [the first satire] looks like a plea for stability and restraint, Horace’s manoeuvres here are paradigmatically restless, self-contradicting and experimental.’

It took a long time to get the hang of this kind of conversational verse in English too. Wyatt made the best attempt in the sixteenth century, in three surviving ‘epistolary satires’ indebted strongly to Horace and dating probably from the late 1530s. These poems are quite unlike anything else in English at the time:

Mine own John Poyntz, since ye delight to know

The cause why that homeward I me draw

(And flee the press of courts whereso they go

Rather than to live thrall under the awe

Of lordly looks) wrapped within my cloak,

To will and lust learning to set a law,

It is not because I scorn or mock

The power of them to whom Fortune hath lent

Charge over us, of right to strike the stroke;3

Although Wyatt’s personal and political circumstances were rather different from Horace’s, and only three of these poems survive, he deals with several similar topics:

Each kind of life hath with him his disease.

Live in delight even as thy lust would

And thou shalt find, when lust doth most thee please,

It irketh straight and by itself doth fade.4

The usual models cited for these poems by Wyatt are Horace, Chaucer and the contemporary Italian poet Luigi Alamanni (1495-1556). I suspect Wyatt may also have seen some of the épîtres (verse epistles) of Clément Marot (1496-1544), most of which date from very much the same period. Like Marot, Wyatt composed sonnets, rondeaux and ballades and — also like Marot — he wrote early and very influential psalm paraphrases as well.5 I have thought for a while that a bilingual edition putting Marot and Wyatt alongside one another would be fascinating, if I suppose a bit niche from a marketing perspective.

It was Jonson of course who really worked out how to do this kind of thing in English. I’ve written about my love for the ‘hexameter’ Jonson quite recently (this is not a literal description of course: Jonson did not actually write in hexameter). Here’s Jonson writing to Sir Edward Sackville, probably in the early 1620s, a period in which Sackville may have helped the poet:

If, Sackville, all that have the power to do

Great and good turns, as well could time them too,

And knew their how, and where, we should have then

Less store of proud, hard, or ingrateful men.

For benefits are owed with the same mine

As they are done, and such return they find.

The first book of Satires was only the first of Maecenas’s many returns for his generosity to Horace: an investment which, remarkably, continues to pay dividends more than two thousand years later.

J. N. Adams, An Anthology of Informal Latin, notes several instances of his ‘fossilized instrumental’, in Cato and in the letters of Augustus (as reported by Suetonius). The instrumental is a case used to indicate the ‘instrument’ by which or with which something is done. It is found in several Indo-European languages, such as Sanskrit and Russian. In Latin, it was absorbed into the ablative case.

Fio is anomalous in other ways too, especially in terms of its sequence of vowels and their relative lengths. Anyone who is interested in the details can consult section 489 in Andrew Sihler, New Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin, from which the quotation is also taken.

The opening of poem CXLIX, addressed to John Poyntz, about whom we know little. Two of Wyatt’s three ‘epistolary satires’ are addressed to Poyntz, the third to Sir Francis Brian, a courtier, diplomat, translator and poet about ten years older than Wyatt.

From poem CL, also addressed to John Poyntz.

Spare a thought for Lucilius, writing conversational Latin hexameters 80 years before Horace, but fragmentary and thus neglected, even by Emily G. I’m being facetious, but Roman sermo didn’t spring forth fully-formed in 35, and Horace himself makes that perfectly clear by explicitly referencing Lucilius and implicitly too,

I like the way you move from word-by-word analysis to broader cultural trends, illuminating both.

Did the earlier French progress in these forms of verse have to do with closer Italian ties (including the invasions)? I know Montaigne's father fought in Italy, for example, and of course there's the Petrarch connection. I visited his hideaway in Fontaine-de-Vaucluse in 2024, and found it an inspiring site, well worth a visit.