Stay lovely boy! Why fly'st thou me?

George Herbert, translation, and the vagaries of literary reputation

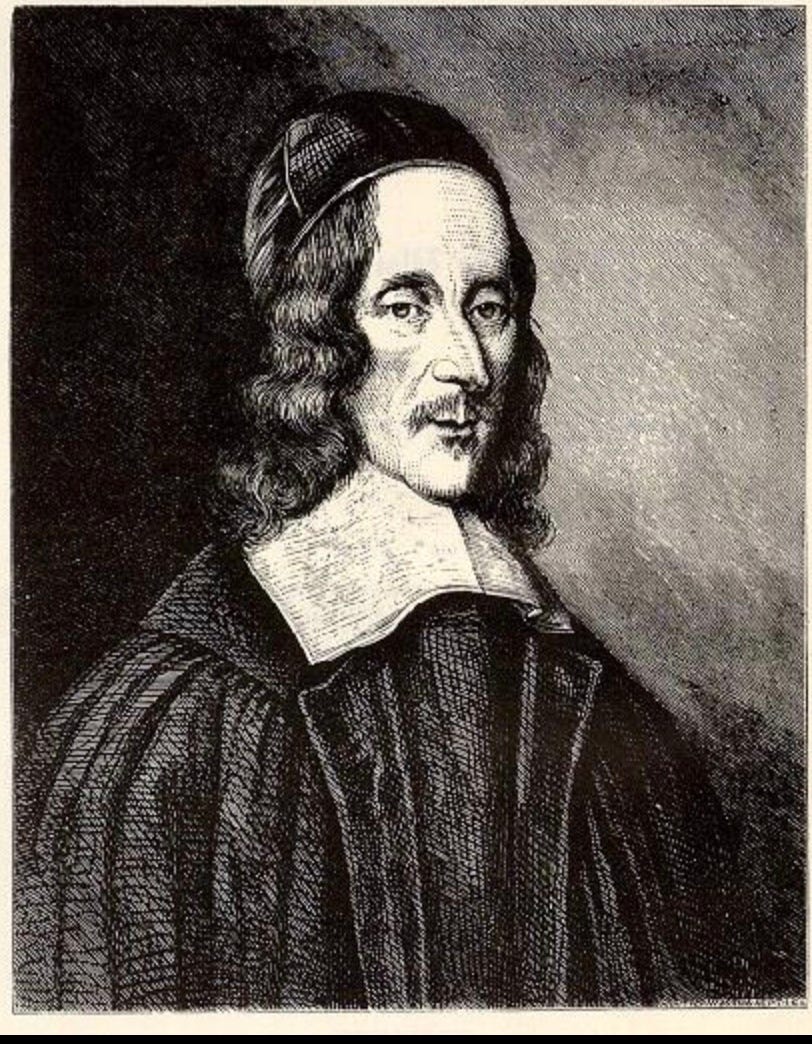

Some works of literature take time to gather a following, and some were plainly a hit from the start. George Herbert’s Temple is an obvious instance of the latter category: there are quite a lot of surviving examples of people reacting enthusiastically and as it were ‘in real time’ to their first reading of it at or shortly after its publication, and its influence upon contemporary poetry was obvious by the middle of the century. The Temple was published in 1633 just after Herbert himself had died, aged only 39, and it was his first and only collection of English verse; during his lifetime, he was known mainly as a Latin poet and orator, and a few of his Latin poems were circulating quite widely in the years before his death.

Several of the earliest responses to the Temple consist of translations of parts of it into Latin verse — a fascinating phenomenon I may come back to another day. But here is one of my favourite mid-seventeenth-century amateur poets, John Polwhele, responding to The Temple and to the news of Herbert’s death either in 1633 or very shortly afterwards.1 I’ve given an exact transcription of his poem as it appears in the manuscript, which is also a fun example of the considerable flexibility of English spelling and punctuation at the period.

On mr Herberts devine poeme the church.2

Jo: Polw: post mortem authoris mestus posuit [John Polwhele. Composed in sorrow after the death of the author]Haile Sacred Architect

Thou doest a glorious Temple raise

stil ecchoinge his praise,

who taught thy genius thus to florish It

wth curious grauings of a Peircinge witt.statelye thy Pillers bee,

Westwards the Crosse, the Quier, and

thine Alter Eastward stande,

Where Is most Catholique Conformitie

Wth out a nose-twange spoylinge harmonie3.Resolue to sinne noe more,

from hence a penitent sigh, & groane

cann flintye heartes vnstone,

and blowe them to their happye porte heauen’s doore,

where Herberts Angells’ flowen awaye beforeJo: Polwheile4

Polwhele pays tribute to Herbert by attempting an imitation of the kind of stanza form typical of The Temple, in a poem which is also a pretty good summary or paraphrase of the message of the collection as a whole. Modern readers tend to downplay, or not notice, the element of partisanship or polemic in The Temple, which contains material aimed against both Puritans and Roman Catholics. Polwhele’s poem, by contrast, puts Herbert’s anti-Puritanism at its heart: the ‘nose-twange’ spoiling the harmony of Catholic conformity refers to Puritans, who were often described at this period as speaking in a nasal way.

Polwhele was a Cornishman born around 1606 who had almost certainly been at Exeter College, Oxford (the traditional West Country college). He entered Lincoln’s Inn in 1623 — a common final stage of education even for those who did not intend to practice law — but he may not have spent long in London. Like any man of his background at the time, Polwhele is at ease in Latin, and there are bits of Latin verse in his notebook and a large quantity of Latin prose compositions (probably school or university work). He was particularly interested in translation from Latin: as well as some translations of contemporary Latin epigrams, the bulk of his notebook is taken up with an extraordinary sequence of translations and versions mainly of Horace and Boethius, often adapted to convey a sharply contemporary message. Polwhele doesnt, though, seem to be much in touch with the sort of fashionable Latin verse for which Herbert was known during his lifetime, and from which — in fact — many of the most striking features of The Temple derive.

But if we look more carefully, the early pages of Polwhele’s notebook actually point to both aspects of Herbert’s fame — as an English religious poet, and as a highly fashionable, often polemical, and not always religious Latin one: the Herbert we know today, and the forgotten Herbert together. Just five pages before the poem about The Temple, we find a poem headed ‘Incerti authoris [by an unknown author]. A song’. This poem is not well known now but it is found in a large number of contemporary manuscripts and is in fact (almost certainly) by Henry Reynolds [or Rainolds].5 Its striking subject is the lament of a black girl who longs for the love of a white boy:

Why louely boy? Why fliest thou me?

that languish in despaire for thee.

I am blacke tis true, why soe is night,

and loue doth in darke shades delighte.

Al the world doe but close thine eye

wil seeme to thee as blacke as I,

or ope, & view what a blacke shade

Is by thine owne faire bodye made,

wch followes thee wher er thou goe.

(Oh who allowed would not doe soe)

Oh for euer let me dwell soe nigh,

And thou shalt want none other shade but I.6

Though almost none of the available scholarly resources or catalogues mention it, this very popular poem, dating probably from the later 1620s, is actually a translation of one of Herbert’s most circulated Latin poems, the enigmatic ‘Aethiopissa’:

Aethiopissa ambit Cestum Diuersi Coloris Virum

Quid mihi si facies nigra est? hoc, Ceste, colore

Sunt etiam tenebrae, quas tamen optat amor.

Cernis ut exustâ semper sit fronte viator;

Ah longum, quae te deperit, errat iter.

Si nigro sit terra solo, quis despicit arvum?

Claude oculos, & erunt omnia nigra tibi:

Aut aperi, & cernes corpus quas proiicit umbras;

Hoc saltem officio fungar amore tui.

Cùm mihi sit facies fumus, quas pectore flammas

Iamdudum tacitè delituisse putes?

Dure, negas? O fata mihi praesaga doloris,

Quae mihi lugubres contribuere genas!

Here is a fairly literal translation:

What does it matter if my face is black? Of the same colour, Cestus,

Is the dark, and love longs for dark all the same.

You see how the traveller’s brow is always burnt:

Ah how long a road does she wander, she who pines for you.

If the land has black earth, who despises the furrow?

Shut your eyes, and everything will be black for you:

Or open them, and you’ll see the shadow your body casts;

This service, at least, I’ll perform for love of you.

Since my face is smoke, what flames do you think

Have been lurking all this time silently in my breast?

Hard-hearted, do you still refuse me? O the fates foresaw my pain,

When they gave me these dark and mournful cheeks.

Rainolds has somewhat simplified the argument and rhetorical detail of Herbert’s Latin, and at one point he unpacks considerably a concise aside: Herbert’s ‘this service, at least, I’ll perform for you’ [i.e., if you let me, I’ll be your shadow] is the basis of the whole last three lines of the English song. But all the same, the English poem is recognisably based upon the Latin. When he copied down the poem, however, Polwhele does not seem to have known either who wrote the English lyric, or that it was a version of a Latin original.

Herbert’s ‘Aethiopissa’, which is so different from any of his famous English religious lyrics — and has surprising elements even if you know his Latin verse well — was written for Francis Bacon, and sent to him, with a dedicatory English poem, as a kind of thank-you in return for a book (described as ‘a diamond to me you sent’), probably part of Bacon’s grand project, the Instauratio Magna, the first portion of which (the Novum Organum) was published in 1620, but which Bacon had been working on for many years.7 All of the early manuscript copies of ‘Aethiopissa’ contain the English and the Latin poems together. Bacon was a family friend of Herbert’s, they had known each other for more than a decade, and several of his other Latin poems in praise of Bacon’s work also had a wide manuscript circulation.

Since English literature written from the perspective of a black person is very rare in this period, the poem has attracted a fair degree of scholarly attention and speculation, not all of it, however, displaying much sense of its cultural context. (Sometimes the fact it was written for Bacon isn’t even mentioned.) Other scholars have interpreted the poem as a kind of formal ‘courtship’ of Bacon by Herbert — in a social or patronage-related way, rather than a romantic one. This doesn’t seem quite right, given their well-established friendship, but there does seem to be something distinctly personal and playful about the combination of the English and Latin pieces. The conceit of the Latin poem is probably inspired by Song of Songs 1:5 (‘I am black, but comely’), a very fashionable text for Latin verse imitation and response at just this period. In addition, though it has not to my knowledge been remarked upon, several of Bacon’s scientific works address the question of why some people have darker skin than others, pointing particularly to the heat of the sun (as mentioned in the Latin poem); since Herbert knew Bacon well, it is likely that he was aware of his interest in this question and they might even have discussed it.8 Overall, though, Herbert seems to be using the girl’s ‘blackness’ and her characterisation as a shadow to comment on the relationship between public office (as held by Bacon) and the relative obscurity of Herbert’s life of scholarship.9 Indeed, many of Herbert’s Latin poems are concerned with the choice between a public and a more private career (whether of scholarship or, later, of ministry).

Polwhele follows the Rainolds lyric with a song by Henry King (though again, he doesn’t know the author) which ‘replies’ to it, in the voice of the boy addressed, explaining his refusal.10 King’s poem is also found frequently at the time and the two poems are often together, as they are here. (Polwhele describes the King poem as ‘sung to the same tune’). Most fascinating of all, though, for the Herbert scholar, is the single line of hard-to-read Latin hexameter scribbled at the bottom of the page:

si tantus facie fumus quas pectore flammas

If there’s so much smoke in [my] face, what flames in [my] breast

This line has never been noted or recognised before, but it is undoubtedly a version of the ninth line of Herbert’s original Latin poem.11 Two more things stand out: first, that this single line of Latin is in the same hand as the rest — so it is certainly Polwhele that added it — but it’s in a paler ink than the surrounding pages, suggesting that it was added at a different time. At some later point, Polwhele probably came across ‘Aethiopissa’ and, recognising that it was the model for the English song he knew well, noted down a memorable line. But the second thing to note is that this Latin line does not correspond to any specific part either of Reynolds poem or of King’s: the point being made here — about a ‘smoky’ (i.e. dark) face suggesting passionate flame within — is one of the conceits Reynolds removed when he transformed the poem into an English lyric. So the relationship between the line and the English poems is quite a complex one. Jotting down this single Latin line at the foot of the page is almost like a reminder to oneself that “there’s more to it”.

A section of manuscript verse dating from the early 1630s which at first seems to bear no trace of the public, ‘Latin’ Herbert, turns out, on closer examination, to contain three distinct layers or types of encounter with his work: first, and unrecognised by the compiler, in the popular song based on ‘Aethiopissa’, and its response; second, in the direct response to The Temple in 1633; and then, at some later point, in an encounter with the original Latin text of ‘Aethiopissa’ — perhaps because Polwhele went looking for other work by Herbert, or perhaps because he came across ‘Aethiopissa’ quite independently, with or without its prefatory poem to Bacon, and, struck by the link, noted down a particularly good line. In just a few pages we have a perfect “worked” example of how even for a reader and amateur poet like Polwhele, living mostly far from London, who composed little or no Latin verse himself, Latin and English poetry were intricately bound up with one another. In a bilingual literary culture like early modern England, you can’t make good sense of “one half” without the other.12

The poem itself is not dated but this section of the manuscript all seems to date from the early 1630s. I use ‘amateur’ in this instance not because he didn’t publish his poetry in print — lots of significant poets of this period were circulated only in manuscript — but because although we have a notebook full of his poetry, there is no evidence that he circulated his verse at all, or had any sort of wider recognition as a poet. It’s also true that his poetry is typically rather awkward and, though often touching and surprisingly powerful, rarely entirely successful technically or rhetorically.

The Temple is divided into three sections: ‘The Church Porch’ (a long moralising poem which was hugely popular in the seventeenth century, though generally ignored today); ‘The Church’, which constitutes the great majority of the collection and contains all the lyric poems for which Herbert is still famous; and finally ‘The Church Militant’, a long and somewhat polemical poem on the history of Christianity — or rather the struggle between true religion and sin — in rhyming couplets.

At this period Puritans were often characterised as speaking in a nasal fashion; this is probably what the ‘nose-twange spoylinge harmonie’ refers to. Polwhele is endorsing Herbert’s ‘Catholic Conformitie’ over Puritan practices.

Bodleian MS Eng. poet. f. 16. Polwhele’s charming notebook of verse deserves a post of its own. One of my favourites is his poem consoling Ben Jonson. I wrote a bit about Polwhele and his ‘Jonsonian’ version of Horace in my first book, Jonson, Horace and the Classical Tradition (CUP, 2010; pbk 2016).

Even by the standards of the period, Henry Reynolds is remarkably elusive. We know essentially nothing about him, though various poems and works about poetry survive in manuscript and print, indicating that he was active, at least, between around 1628 and 1632.

This is a (slightly tidied) transcription of the poem as it appears in Polwhele’s manuscript, fol. 8v. This version is actually somewhat different from the printed version (it wasn’t published until 1657) or other manuscript copies, suggesting a considerable degree of oral transmission. There are surviving musical settings as well, and various features of Polwhele’s copy suggest that he may indeed have heard it sung rather than seen it written.

E.g. Historia Naturalis (1622), Cent. IV. 399, which mentions Aethiopia in particular.

This might suggest that the poem dates from before Herbert became University Orator in 1620. Bacon, addressed as Lord Chancellor in the English poem, took up that office in 1618.

A version of line 9, substituting ‘Si tantus facie fumus’ for ‘Cum mihi sit facies fumus’. Polwhele’s version is arguably better as a stand-alone line though the original ‘cum mihi sit facies’ echoes the first line of the poem (‘quid mihi si facies’). This is real, live scholarship folks (I only noticed recognised what this line was this morning). I haven’t published this yet in any scholarly note or article though it will probably go into a chapter I’m working on at the moment. I have not yet had a chance to collate this reading against the known MS copies of ‘Aethiopissa’, to see whether any of them have the line in this form, but I don’t think they do.

Herbert’s Latin verse, like that of so many of his contemporaries, deserves to be better known, but unlike most other Latin writers of this period, his is actually moderately accesible. Some years ago I worked with John Drury on a Penguin edition of Herbert’s poetry, and (amazingly) we managed to convince Penguin to publish the complete Latin as well as English verse (plus the handful of Greek poems) with parallel English translations and brief notes, all in a single manageable volume. The edition is still available and though there are a handful of things I’d do differently now, and we were forced to keep the notes very brief, it’s a rare and commendable example of early modern Latin literature available to the general reader at a reasonable price.

I’ll confess I read this as a sleep aid- I had galloping insomnia and it looked dry as dust. How wrong can you be. Beautiful and fascinating.

Really enjoyed this! How different from our own culture of versions and “after” poems, where the assumption is usually that the reader *can’t* read the original.

(I’ll have to buy that Herbert book now; I had no idea it included the Latin poems!)

When I started learning Latin, I did so with the intent of reading the classics. That’s still my main motivator, but over time I’ve also become interested in Neo-Latin. As an Indian I hoped I would feel an affinity with a bunch of late arrivals in a literary tradition operating somewhat artificially within a lingua franca, but the more I learn the weaker that prospect of affinity grows. There’s too much distance between us and them. Still, that’s its own source of fascination, maybe a more profound source.