Discover more from Horace & friends

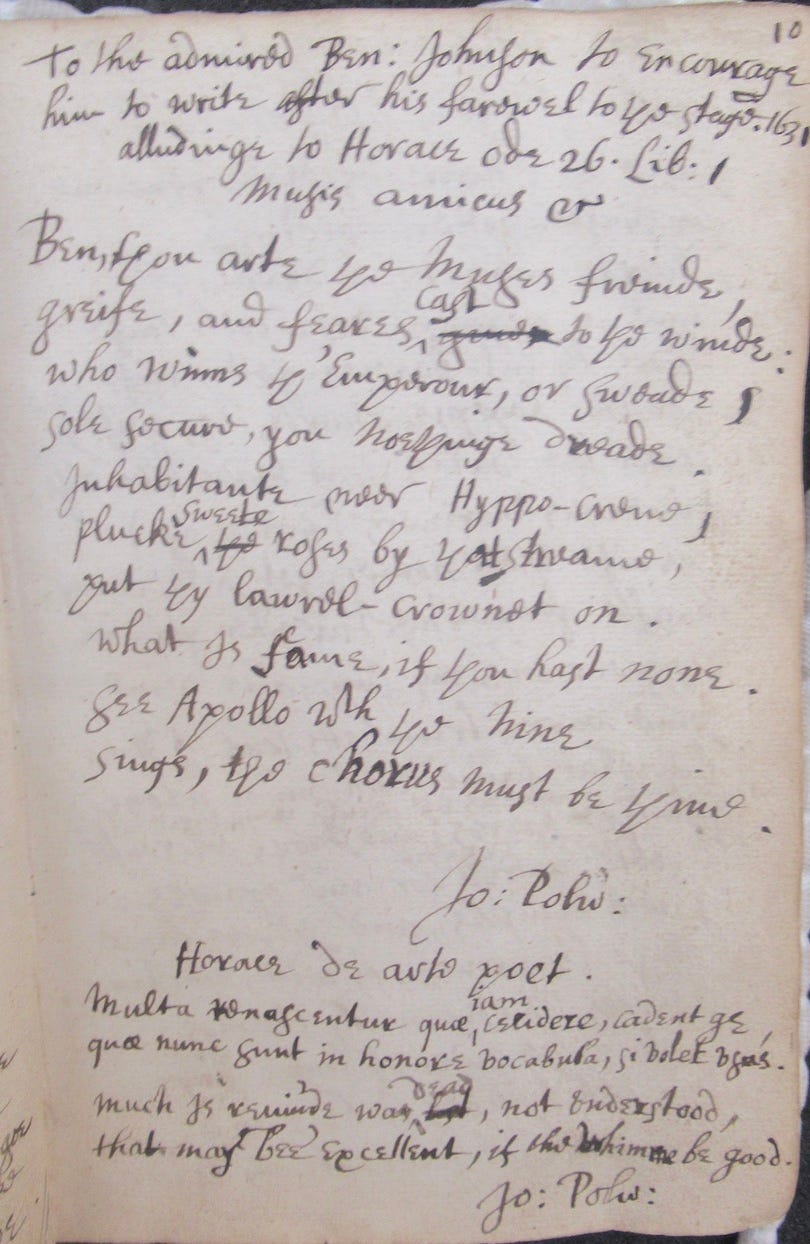

John Polwhele was born in about 1605 and died in 1672 — he came from Cornwall, and spent most of his life there, settling in St Erme with his wife Anne Baskerville after a few years first (probably) at Exeter College, Oxford — the traditional college for students from the West Country — and then at Lincoln’s Inn.1 Other than that, we know almost nothing about him. All that is left is a single notebook, inherited from a friend, Joseph Maynard, probably in the later 1620s — Maynard went on to be rector of Exeter College, Oxford in the 1660s. I first looked at Polwhele’s notebook either as a doctoral student working on Ben Jonson, or immediately after my doctorate, when I was a Junior Research Fellow (a kind of post-doctoral position) in Oxford, rewriting my PhD dissertation as a book.2 At first glance, it is rather unprepossessing. These are the opposite of neat drafts, and even at his neatest Polwhele’s hand is best described as a scrawl:

Once I began transcribing him, though, I was won over. Some of the ‘voices from the archive’ that you encounter in manuscript are so vivid and become so real that it is almost like a kind of relationship, and I think this is especially true when you work over a long period of time on essentially intimate documents like this notebook, which were obviously never intended for circulation. I have gone back to Polwhele repeatedly over the last twenty years, and especially to his impassioned translations of Horace and Boethius made during the English civil war.

The notebook doesn’t start with translation, though. The first entries, which seem to date from the late 1620s and 1630s, consist mainly of other people’s verse and suggest a man staying keenly in touch with contemporary literature, even though he was himself almost certainly back in the West Country by then, far from the London stage or courtly performances. The first poem is a copy of a very popular — almost ubiquitous — satirical poem about the Duke of Buckingham, dating from 1627 or 1628.3 The rest of the opening sequence of entries give a similar impression of a man keeping up with literary fashion — it includes, for instance, a very popular song, the ‘Prayer for King James’, from Ben Jonson’s masque The Gypsies Metamorphosed as well as a (less commonly found) song from a play, the Northern Lass by Richard Brome — a man who been Jonson’s servant before becoming an author, and who may himself have come from the West Country.4 There are a lot of songs altogether, and Polwhele seems particulary fond of music. Like Herbert, he uses musical metaphors very frequently in his poetry. One of the best examples is the rather charming lyric addressed ‘To To Mrs M: E. who sange to her Lute’:

Noe more of this eare-lecherie! lay bye

that guidled lute!

and let her voyce be mute

Tune vp those veines for natur’s harmony

that euerie sinewye touch

may in our mutual sympathye be such

as when two vyols by on hand doe moue

ther Is noe musick like consorte In Loue.Entreatyes cannot silence, yet extorte

Musical ayres

from harpes stringe wth a thousand haires

for the blinde Harper, amarous Cupide, sportes

who steals this waye more hearts

then conquers by his golden-headed darts:

woemen ar his best Instruments to proue

ther Is noe mysick like consorte In Loue.5

Polwhele also copies out one of the most popular poems of the period, ‘If shadows be a picture’s excellence’, which he attributes to John Donne (though modern scholars now consider it to be by Walton Poole), as well as the English translation by Henry Reynolds of George Herbert’s ‘Aethiopissa’, on a similar theme, which I have discussed here.6

But what’s really touching about Polwhele in these pages is not the exercise of his fashionable good taste, but his sense of connection to the authors he admires. One of the few poems of his that has been printed repeatedly is his little piece in admiration of George Herbert’s Temple (published in 1633, and which I also discuss in the ‘Aethiopissa’ piece linked to above). But it’s not only Herbert whom he addresses in this way, and in fact his sense of Herbert’s personality and authorial identity seems relatively remote. By contrast, in a poem lamenting the death of Sir John Elliott, ‘who died a prisoner in the Tower of London, 1631’, Polwhele addresses John Donne directly:

Donne! Had this rival preached in thy quire,

All would not seek heat from thy holie fire.

Barke not at his urne, Cynick: if you doe,

He that smiles praise, can frowne Iambicks too.

Only the noble spirits may complain,

That they hath found a harder way to fame.7

The most touching of these tributes to a contemporary literary figures, however, is a brief one addressed to Ben Jonson, dating also to 1631. After the accession of King Charles I in 1625, Jonson fell rather out of favour and the final decade of his career subsided into failure and disappointment, including the production of disastrous new stage-play, The New Inn, in 1629. Jonson took the failure of this production personally, and his bitter ‘Ode to Himself’ announcing his retreat from the stage circulated extremely widely. Polwhele’s poem is a kind of reply to Jonson’s ‘Ode to Himself’, to encourage him to continue to write (if you want to see what the manuscript page looks like, this is a transcription of the image above):

To the admired Ben: Johnson to encourage him to write after his farewel to the stage. 1631

Alludinge to Horace ode 26. Lib: 1, Musis amicus &cBen, thou arte the Muses freinde,

greife, and feares, castgiveto the winde:

who winns th’Emperour, or Sweade

sole secure, you noethinge dreade.

Inhabitante neer Hyppo-crene,

plucke ^ sweetetheroses by that streame,

put thy lawrel-crownet on.

What Is fame, if thou hast none?

See Apollo wth the nine

sings, the chorus must be thine.8

Polwhele doesn’t give the Latin of Horace, Odes 1.26 in full, but we are meant to remember it.9 Polwhele has replaced Horace’s first-century BC references to the manoeuvres of the Medes and Dacians with ‘the Emperor’ and ‘the Swede’, referring in the latter case to King Gustav Adolf of Sweden, who joined the Thirty Years’ War in 1630, and in the former to the Hapsburg Emperor of the Imperial League. Horace’s three-stanza poem is divided in two, switching in the middle of its second stanza between the first person with which it begins (‘I, as the Muses’s friend, consign grief and fear to the winds . . .’) and the second person of the invocation to the Muse to whom he modestly, if perhaps disingenuously, defers his achievement and the beauty of the ‘crown’ (that is, the poem) he weaves for Lamia. Polwhele’s little version on the other hand makes both the ‘I’ and the ‘you’ of Horace’s poem, that is both Horace and the Muse, Jonson himself. The love-object of the original poem, the boy Lamia, has disappeared completely, and Jonson himself is incited to put on the version of Lamia’s wreath, here the ‘laurel-crown’ of the great poet. Polwhele’s tender little poem does Jonson the honour of making him Horace, the Muse and a beloved boy all at once. But there is no evidence whatsoever that Polwhele knew Jonson, any more than he knew Donne, Herbert, or indeed Horace himself.

In the late 1640s, and prompted especially by the execution of Charles I in 1649, Polwhele turns abruptly from this kind of cultured miscellany of contemporary verse and personal adaptions to an intense phase of translation. This extraordinary sequence contains a large number of heavily revised and explicitly politicized versions of Horace and the metrical portions of Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy, a work written by Boethius in prison in 523, as he awaited execution at the hands of the Ostrogothic king Theodoric.10 In a typical example, Polwhele expands and elaborates some rather generalising lines from Boethius Consolation of Philosophy 1. met 5 on the injustice of fortune. The Latin here runs as follows:

nam cur tantas lubrica versat

Fortuna vices? premit insontes

debita sceleri noxia poena,

at perversi resident ceslo

mores solio sanctaque calcant

iniusta vice colla nocentes.

latet obscuris condita virtus

clara tenebris iustusque tulit

crimen iniqui.

(29-36)

This means:

For why does slippery fortune so often reverse things? The innocent endure the pains that are properly the punishments for wickedness; evil practices occupy the lofty throne and wicked men trample underfoot sacred necks, in an unjust reversal of fortune. The clear brightness of virtue lies hidden in darkness, and the righteous man is charged for the crime of the wicked.

This is what Polwhele has, for these lines — and in this case I have kept as close as possible to an exact transcription, to give a sense of the intensity of revision:

what there doth waninge fortune meane

so frequently to shifte her sceane?

due to the guiltye punishment’s

Inflicted on the innocents

Ostro=barbarianGothes doe tread uppon

theIndependent mounts the throne

most sacred necks to mounte the thronebeheads the Lords annointed one

Patritians in exile hidethe king, & Peerres exild abide,

att homethe Loyalliststrue Patriots haue died

for treason.11

Such a version bears only a remote resemblance to the original. Nothing in the Latin corresponds to ‘behead the Lord’s anointed one’, which obviously refers to the execution of Charles I, just as ‘the Independent mounts the throne’ refers to Oliver Cromwell.

These heavily revised versions of Latin verse give a powerful sense of how one man experienced a moment of national crisis. The best of them is his version of the ship of state poem, Horace Odes 1.14, a lyric which was much imitated at this period. (Andrew Marvell’s great poem, ‘The First Anniversary of the Government under O. C.’, for instance — though written as it were from the other side — draws upon the same ode.) I’ve even written a (very loose) version of the poem myself.12 Here is Horace’s Latin:

O navis, referent in mare te novi

fluctus. O quid agis? Fortiter occupa

portum. Nonne vides ut

nudum remigio latus,et malus celeri saucius Africo

antemnaque gemant ac sine funibus

vix durare carinae

possint imperiosiusaequor? Non tibi sunt integra lintea,

non di, quos iterum pressa voces malo.

Quamvis Pontica pinus,

silvae filia nobilis,iactes et genus et nomen inutile:

nil pictis timidus navita puppibus

fidit. Tu, nisi ventis

debes ludibrium, cave.Nuper sollicitum quae mihi taedium,

nunc desiderium curaque non levis,

interfusa nitentis

vites aequora Cycladas.

Here is the first of Polwhele’s two versions of the poem. This poem, like most of Polwhele’s verse, is quite easy to criticise — his poetry is often metrically eccentric or uncertain, and the syntax can be awkward. But it has a real power and I find the last stanza, addressing the ship (that is, the nation) itself very moving.

I have kept Polwhele’s erratic capitalization and spelling, and almost complete lack of punctuation, which conveys something of the urgency of his version, though I have added some notes on the meaning of words. If it seems difficult to follow, try reading it aloud - and it might be useful to know that, syntactically, Polwhele treats the end of the longer first and second lines as a break also in syntax and meaning, but typically treats lines 3 and 4 as a single unit.

Horace lib: 1. Ode 14 an Allegory to the people of Rome repayring the breaches of Ciuell war, with newe auxilliaryes.

poore Hulk, wilt launch in a new storm? o stay!

careene13 & calk14 thy leaks in a safe bay

look on thy naked banks15 no oare

where sun=burnt rowers tug’d before!neere treacherous Aegypt thy mayne mast did wrack

hark how the Helm, misne16, Prowe in Tyber crack!

thy Cabell spent, the giddy keele

drunck wth impetuous waues doth reelestrik thy top=gallant17, & the tatterd sayle

to thy deafe Sea=Gods, who thee nought avayle

though built of Pontick pyne, wch stood

the tallest ofspring in the wood.That ancient stock, & empty name n’er bost

pylotts in storms trust not a gilded post

Cast Anchor (if thou canst) beware

the scornfull Hurrycanes to dare.distressed Gallye thou wert late my feare

but now my Joyfull Hope, & tender Care

veere o veere ho, the straights, & seas

betweene aspiring Cyclades.18

This rather effective version of Horace’s poem blends sorrow and hope, and makes a few key alterations to the Latin: in the second stanza you can see that Polwhele has added references ‘Tiber’ and to ‘treacherous Egypt’ — suggesting the stand-off between Octavian and Antony and Cleopatra — to emphasise the suggestion of civil war. These aren’t in the Latin poem itself, though Horace’s ode has traditionally been interpreted as referring to these events. The winds of Horace’s poem have become “scornfull hurricanes” at the end of the penultimate stanza, and the ‘nitentis Cycladas’ with which the Latin poem ends are — strictly speaking — mistranslated by the suggestive, but enigmatic, ‘aspiring Cyclades’. (Polwhele has confused two Latin verbs, niteo meaning shine and nitor meaning strive — the Cyclades are actually shining here, though the mistranslation is rather effective in the context of the political allegory, implying the various rival factions in a period of rapid political transition.)

This translation is undated in Polwhele’s notebook, but its position in the book suggests that it dates from the early 1650s — perhaps at some point during the Anglo-Scottish ‘Third’ Civil War of 1650-1652, when Polwhele (whose sympathies are clearly royalist) felt that things might go either way.19 In any case, it’s hard to read either Horace’s poem, or Polwhele’s version of it this week without thinking of the hopes and fears of the people of Syria, another country waiting to find out whether it is emerging from, or falling back into, the tragedy of civil war.

He was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn in 1623, as a ‘special admission’, meaning an admission granted with certain privileges and exemptions. The evidence for his presence at Exeter College is more circumstantial as his name does not appear in the Alumni Oxonienses, but there is a striking overlap between the names mentioned in his notebook and alumni of the college — including John Eliot, William Strode, John and Joseph Maynard, Sir John Arundel, Sir Bevil Grenville and Joseph Glanvill as well as several other members of the Polwhele family. See William Keatley Stride, University of Oxford — College Histories: Exeter College, pp. 55-71. John’s sons John and Thomas matriculated at Exeter in 1658 and 1662, respectively; Thomas was a fellow of the college between 1664 and 1678. In 1677 he became vicar of Newlyn East, Cornwall, but was deprived as a Jacobite in 1690, as a Jacobite.

The manuscript is Bodleian Eng. poet. f. 16. The book I was working on appeared as Jonson, Horace, and the Classical Tradition (CUP, 2010; pbk 2016). Also in the Bodleian is the script of a masque by one Elisabeth Polwhele, an interesting example of female dramatic authorship at the period (MS Rawl. poet. 195). It is unclear whose daughter Elisabeth was, but given John’s royalist sympathies and demonstrable interest in courtly music and drama, it seems quite likely that she might be his.

Like many of the most popular satirical poems, this piece circulates in a myriad of slightly different versions. You can read the poem here.

See Martin Butler, ‘Brome, Richard (c. 1590-1652), ODNB. The Northern Lass was first acted in July 1629 and publised in 1632.

Eng. poet. f. 16, fol. 1v. I believe this poem has only been published once before, in Peter Davidson, Poetry and Revolution: An Anthology of British and Irish Verse, 1625-1660 (Oxford, 1998) — in my view the best single anthology of poetry from the mid-seventeenth century.

Polwhele titles the piece incerti authoris (‘of an unknown author’), but at some later date he added a line of Herbert’s Latin poem at the bottom of the page, suggesting that he eventually realised that it was based on Herbert’s poem.

Eng. poet. f. 16, fol. 13r. I have edited this transcription to make it easier to read and understand.

Eng. poet. f. 16, fol. 10r.

Of Horace, he translates Odes 1.14, the ship of state poem, twice, as well as 1.33, 4.9, Epodes 5, 7 and 16, and Epistles 1.18. There are twenty translations from Boethius, Cons. 1. met. 2-7, 2. met. 1-8 and 3. met. 1-6. Stuart Gillespie has published an edition of all the Horatian translations (only), with a brief introduction (‘John Polwhele’s Horatian Translations’, Translation and Literature, 30 (2021), 52-71. Gillespie has tidied up the transcription a good deal in his edition of this poem.

Eng. poet. f. 16, fol. 18r. A fascinating contemporary version of a similar project, with an unusual modern example of an early-modern style title, is Peter Glassgold, Boethius. The Poems from On the Consolation of Philosophy. Translated out of the original Latin in to diverse historical Englishings, diligently collaged (World Poetry, 2024).

Careen means to turn a ship on its side in order to repair it.

To caulk is to stop up the seams of ship, with pitch or tow, to stop it leaking.

I.e. the rowers’ benches.

The mizzen (here misne) is either short for the mizzen-mast, or it refers to the main sail on the mizzen-mast.

The top gallant is the highest sail on a ship; to strike a sail means to lower it.

Eng. poet. f. 16, fol. 51v.

One poem on fol. 46r is dated 1650, and another on fol. 57v is dated 1655.

Subscribe to Horace & friends

Thoughts on poetry, translation and related matters.